From The Sentry

Movie Review: Pixar's Soul

Image courtesy Disney

This article originally appeared in The Sentry CU Denver’s premier source of campus and community news for students and members of the university community.

Written by: Tommy Clift

Even the host of hardships abrading the past year has not stopped Pixar from rolling out another gem to keep people in touch with what’s worth cherishing. Soul, released on Christmas, takes the genius of Inside Out on emotional complexity and applies it to the even more labyrinthine realm of the soul. But unlike Inside Out, which wholesomely characterizes a subject that is put under the microscopes of many psychological studies, this film offers a gateway into something that is far more elusive, and dangerously underrepresented by many overly-secularized cultures.

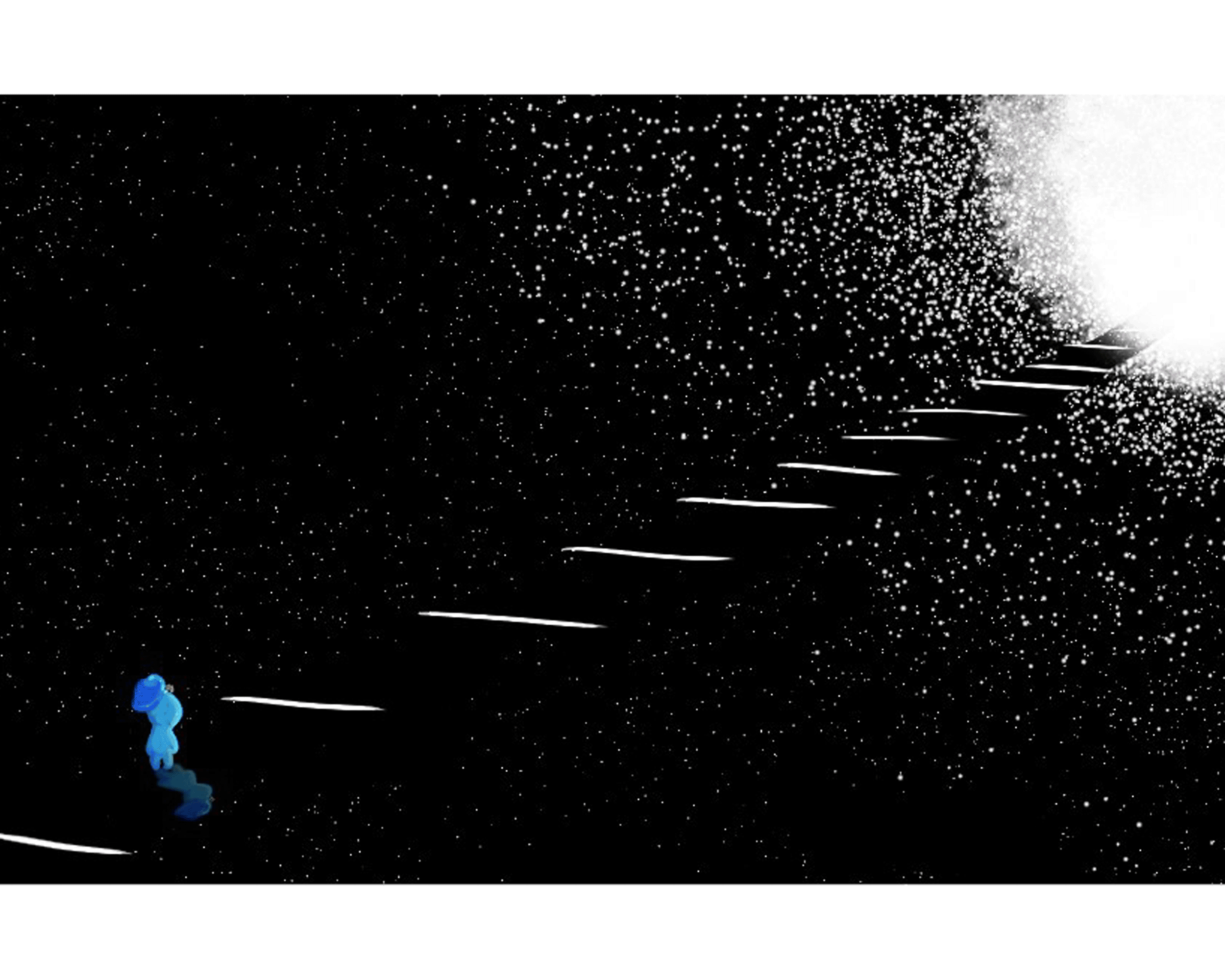

The film introduces Joe Gardner (voiced by Jamie Foxx), a talented jazz cat who—unable to land his big break—is stuck trying to inspire a largely tone-deaf secondary-ed classroom. Just as he grows disheartened by a full-time offer at the school, a call from a former student rings with a chance to fill in accompanying the acclaimed Dorothea Williams ensemble. After entering “the zone” and blowing away the group, he’s invited to perform that night. Breaking into an ecstatic march, he recklessly dashes through the Manhattan streets—until he plummets through an open sewer grate. Now on a dark, fretted Trav-O Lator, the plump blue embodiment of Joe’s soul is moving steadily towards the great beyond—where souls slowly float into a great light, igniting in an electric sizzle like a bug zapper. In utter disarray, Joe flees from the light until he plum mets even further into “The Great Before,” a realm where new souls garner personalities and—once seasoned with a spark—are sent to their mortal “meat suits.”

As Joe sits in the mentor tutorial in The Great Before, just as the introductory video brushes into the subject of the spark, Jerry—a playful name given to “the coming together of all quantized fields of the universe” is narrating this tutorial. He asks the mentors, “now, just what is this spark?” Of course, Joe tunes out—plotting how to rob a soul of its pass to Earth so he can make it to his big gig. The film centers around him and 22 learning what the spark is for themselves—a journey that many viewers may be in need of.

Illustration by: Tatianna Dubose

Joe—looking to return to Earth through the portal new souls take— ends up mentoring 22, a soul who has yet to find her spark, despite coaching from thousands of famous impactful souls like Mother Teresa and Muhammad Ali.

In their partnership (a bargain so that 22 can skip life and Gardner can get his long-desired shot as a gigging jazz cat), the film is charting a clear trajectory about finding a vocational passion—but it ends up circling around something far more potent, a Pixar paradigm.

Westernized education centers around finding a passion from a very early stage. But these passions aren’t about the soul, they’re about a job and societal agendas. It’s a privileged concept—that work must be what a person is completely passionate about. If it isn’t the one thing that motivates, then why do it? But much of the world must work to survive rather than from a source of passion, and what then? Where is the spark to be found?

As 22 searches for a passion on Earth, she cites sky-watching and walking as the greatest purpose of her life, to which Joe replies, “those aren’t really purposes, 22, that’s just regular old living.”

One of the most fascinating astral planes explored is where the lost souls of the Earth wander outside of their bodies. Longwind (voiced by Graham Norton), a kooky Sign Spinner on a New York street corner on Earth, sails this plane where the souls of self-absorbed stock brokers and video game addicts alike have manifested into gloomy, fear-driven creatures. But this place also hosts all of those who are in the zone—that ethereal place people like Joe transcend to when they are acting out their passion. Longwind notes those in the zone and the lost souls are not so different from one another, in that they are similarly “obsessed with something that disconnects them from life.”

As children are raised on this quest for passionate occupation, they are trained for a type of emotional gratification based on a finite number of future events: academic achievement, graduation, hiring, promotion, the first big gig. And children who can tell this doesn’t suit their interest are often left with a deep internal struggle of how to be happy, much like 22, but Pixar points out that this gets just as hazy on the other side.

Feeling his life was meaning less, Joe stakes music as his only real purpose and reason for existence. So when he finally gets his shot, the moment he’s been striving for most of his life, after the gig is finished— the warm gun of happiness fades, and he’s left thinking, this is it?

The anticipation woven into the fabric of ambition occupies so much of a person’s mind that it becomes lost. The film is a reminder that this cultural connection between a job and happiness subliminally planted into the minds of so many is losing sight of where the real practice of happiness is—it’s losing sight of the soul.

“A spark isn’t a soul’s purpose!” one Jerry says to Joe towards the end of the film, “Oh, you mentors and your passions, your purposes, your meanings-of-life—so basic,” Yet there’s an irony in that the film’s answer is basic in its essence—but infinite in its implications.

What then do the scraps of purpose look like? The crust of a good pizza, the thread of a beloved father’s old jacket that their mother tailored for them, these are the remnants of fulfillment, the mark of truly being alive—this is the spark.

Soul preaches that this rapture doesn’t have a single lesson plan. Some do, in fact, develop a quick and eager drive through their goals for life. But for others like 22—no activity nor lecture from the thousands of brilliant and inspired minds will acquire them a spark for life. That spark will be found in the quiet curiosity and consciousness for the world around them.